ARCHIVE FOR THE ‘servitization-2’ CATEGORY

May 16, 2019 • video • Features • Astea • Kris Oldland • manufacturing • Video • field service • Internet of Things • IoT • Servitization • John Hunt

May 09, 2019 • video • Features • Astea • Kris Oldland • manufacturing • Video • field service • Internet of Things • IoT • Servitization • John Hunt

May 09, 2019 • Features • Management • Servitization

The growing digital transformation is blurring industry boundaries and altering established positions of firms. While manufacturers are investing strategically in data collection, analytics capabilities, and in cloud-based platforms, many firms remain concerned about how to best address digital disruption and enable digitalization.

Last year, General Electric cut expenses by more than 25% at its digital unit responsible for Predix, its software platform for data collection and analysis, which previously has been hailed as a revolutionary driver for Industry 4.0. This move highlights the difficulties involved in adopting digital technology in an industrial business.

Having worked with B2B firms in diverse industries on designing and implementing service-growth p84 strategies, we have seen both highly successful and unsuccessful cases of what we call ‘digital servitization.’ Why do firms with a proven track record of running successful field service organizations struggle with implementing digitallyenabled services?

Before looking at some key challenges, let us first define what we mean by digital servitization. As a start, we need to distinguish between digitization, which means turning analog data into digital data, and digitalization, which refers to the use of digital technology to change the business model. A tech-savvy firm with a product-centric mindset may have little difficulty in implementing digitization, as when record companies moved from selling LPs to CDs. However, rather than embracing the new digital opportunities that changed the way we interact with music, most record companies then clung on to a product-centric business logic of selling CDs. Instead of developing business models based on Internet distribution they promoted new physical media like the Super Audio CD.

Ironically, their defensive stance—manifested in such things as copy protected CDs—forced many people to illegal downloading in order to conveniently access MP3 music, thereby undermining their product-centric model even further. Digital servitization, then, refers to the utilization of digital technologies for shifting altogether from a product-centric to a service-centric business model. Of course, digitally-enabled services are not new; for example, Rolls- Royce’s archetypal solution TotalCare began in 1997 and BT Industries (since 2000 part of Toyota Material Handling) created its software system BT Compass in 1993, to help its customers improve their performance.

Likewise, leading bearings manufacturer SKF started early on remote monitoring bearings usage data flowing 24/7 from industrial customer’s equipment installed around the globe. Digital technology, however, can be a double-edged sword. For example, many manufacturers have been carried away by the technical possibilities of telematics without having a clear service business model in mind. Rather than crafting a compelling value proposition based on enhanced customer performance, it was tempting to give the service away for free with the hope that customers eventually would discover the value of data access and be willing to pay for it.

There are however at least three problems with such a technologycentric approach. First, as the connected installed base grows and the costs of collecting and managing data increase year over year, it becomes more and more difficult to defend the model unless service sales start to materialize. Second, giving services away for free always reduce the perceived value of the offering in the eyes of the customer. Why should they pay for something that was previously free of charge and that competitors may still be treating as

a commodity and giving away?

"The growing digital transformation is blurring industry boundaries and altering established positions of firms..."

Third, customers typically do not have the time nor the skills to thoroughly analyze data collected and take appropriate corrective actions. The real value of data and analytics lies in a company’s ability to identify and implement adequate changes. By collecting and analyzing data across multiple customers, a supplier may know more about the customers’ equipment and operations then they know themselves.

Benchmarking performance across industry applications and customers thus provides attractive opportunities for new advanced advisory services. The digital dimension of service growth requires purposeful and coordinated effort. As we know, while manufacturing and conventional R&D activities can be centrally managed to achieve efficiency and standardization, services require increased local responsiveness and closer customer relationships. During digital servitization, however, the central organization must take a more proactive leading role to ensure platform consistency and data quality, to provide the requisite data science skills, to support local units, and to address cyber security issues.

The 2017 large-scale cyberattack (NotPetya) on Danish shipping giant Møller-Maersk, which shut down offices worldwide, illustrates the dangers of inadequately managing the latter issue. Viewing data as “the new oil” is a frequent claim these days. Like oil, data is a source of power. It is a resource used to fuel transformative technologies such as automation, artificial intelligence, and predictive analytics. However, unlike oil, data also has other properties.

We are currently seeing a shift from scarcity of information (data) to abundance of it. Data can be replicated and distributed as marginal cost, and competitive advantage can be achieved by bringing together new datasets, enabling new services. But this also creates new tensions between companies regarding the issues of generation, collection, and utilization of data. If a customer is generating massive amounts of data collected by a supplier, then once processed, it can be used for better serving also the customer’s competitors. In other cases, we are seeing completely new entrants emerging and collecting data on behalf of their clients.

Digitalization is beginning to have a profound impact on even the most stable businesses. Customers increasingly expect a single provider to integrate individual components and products into a system, and that they will do so through one digital interface.

Whether the platform provider is one of the established OEMs, or a new software entrant, often does not matter to customers. Competition may come from unexpected sources, as for example when one of the leading international standards organizations in the marine industry recently moved into platform-based services. Oftentimes, the most formidable threat comes from disruptive innovators outside the traditional industry boundaries.

An executive in a leading incumbent firm stressed that her main concern was not the competition from any established player. Instead, what kept her awake at night was the prospect of Amazon entering—and reshaping—the market. While many share the concerns of being overrun by new competitors, the threat is most imminent to those firms that lack service leadership and a clear roadmap for service growth. To conclude, no firm can afford avoid strategically investing in digitalization.

However, as firms compete in the digital arena, there is a risk that focus shifts too much away from service and customer centricity to new digital initiatives and units. Ten years ago, many executives sang the praises of servitization. Today, digitalization is the poster child for business transformation. Given the rapid pace of innovation, it may be tempting to launch new concepts as soon as the technology is available, rather than waiting until the they have been properly piloted and customer insights gained.

To reap the benefits, firms also need to understand back-end and front-end interactions, investing in both back-end development for enhanced efficiency and better-informed decision-making, and front-end initiatives to enable new services and closer customer integration. Correctly designed and implemented, digital servitization provides benefits for companies, networks, and society at large. Successfully seizing digital opportunities, however, requires more, not less, service and customer centricity than before.

Dr. Christian Kowalkowski is Professor of Industrial Marketing at Linköping University, Sweden, and the author of Service Strategy in Action: A Practical Guide for Growing Your B2B Service and Solution Business. Find out more on www.ServiceStrategyInAction.com.

Dr. h.c. Wolfgang Ulaga is Senior Affiliate Professor of Marketing at INSEAD, Fontainebleau, France. He is the author of Service Strategy in Action: A Practical Guide for Growing Your B2B Service and Solution Business. He also authored Data Monetization: A Practical Roadmap for Framing, Pricing, and Selling Your B2B Digital Offers.

May 06, 2019 • Features • Jan Van Veen • management • more momentum • Servitization

For the next years, many manufacturers will focus more on “how to servitize”: How to make these innovations successful? How to accelerate these transitions and stay ahead of the pack? How to escape from “business as usual”? How to prepare the organisation for such journeys? In this article, I will share an overview of critical challenges and strategies for servitization.

Servitization is a different ball game

Many manufacturing businesses have made good progress in building a common understanding and commitment to business innovation including servitization, and they have allocated resources and funding for servitization.

Now, they are experiencing that servitization is a different ball game from usual innovations and face new challenges, such as:

• Political discussions when deciding on nitiatives and investment

• New risks from uncertainty and unpredictable trends

• Forces towards ‘business as usual, with signs like “not invented here”, “that does not work in our industry”, “our clients don’t want that” and/or “this is not our core business”

The central question: How to organise for servitization

We hear and read a lot about new (digital) technologies, new disruptive business models and servitization. However, the real challenges are about organisational and human aspects:

1. How to translate these general insights into concrete and relevant initiatives?

2. How to overcome the challenges and obstacles and increase momentum?

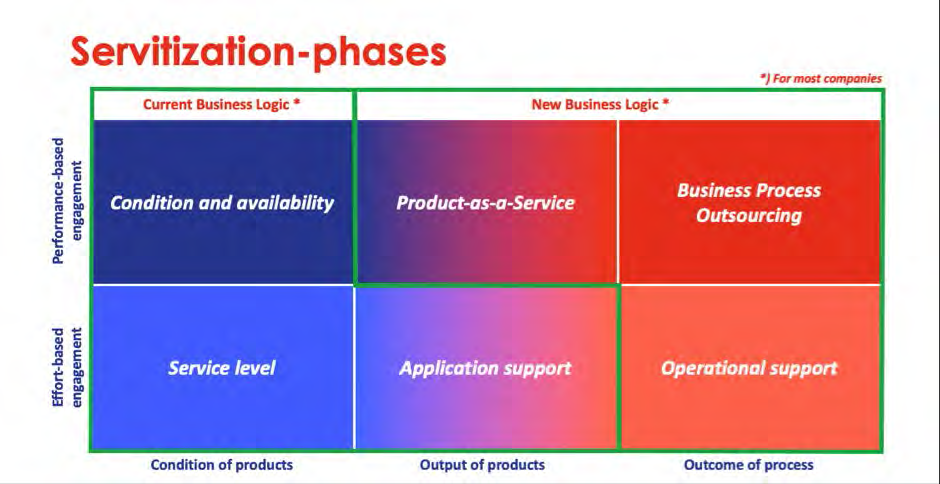

In essence, servitization is innovating your business model, particularly when you move beyond “condition of product” related services. We need to rethink our value proposition, our target market, our position in the value chain and in the competitive landscape. We will be facing new opportunities and new risks. This requires us to be open to new thinking, new mindsets and different strategies for innovation and change.

The problem: One innovation approach doesn’t fit all

Too often, we see successful strategies for one type of innovation being applied for other types of innovation also and therefore fail.

Before diving into best practices, let us first better understand the challenges in different phases of innovation: 1) discovery, including ideation, 2) decision-making, including resource allocation, and, 3) implementation, including development.

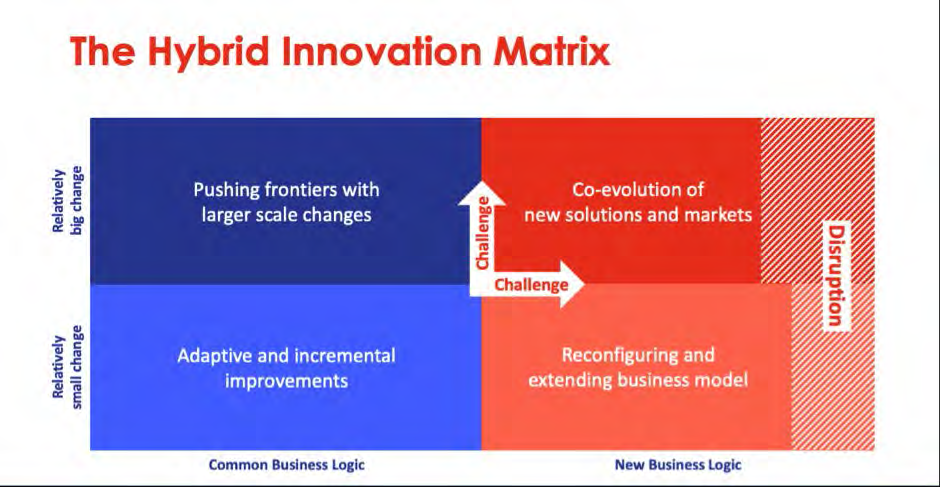

The “Hybrid Innovation Matrix” helps to recognise different types of innovation based on respective typical challenges so we can better choose the best strategy for each.

About the “Hybrid Innovation Matrix”

The “Hybrid Innovation Matrix” (see following page) differentiates four types of innovation with the respective challenges and strategies along two dimensions. Along the horizontal axis, we differentiate innovations within the existing business logic from those developing new business logic. In every industry and business we have prevailing business logic, which is a set of common patterns, knowledge, experience and frameworks of thinking. We use this logic to understand our environment and make decisions. This common business logic defines how we act, learn and change.

Our brains are hardwired to maintain a cognitive framework to rapidly assess their environment, filter information and make decisions. This results in a strong bias towards protecting the established business logic.

Along the vertical axis, we have the relative size of the innovation or change. In the left column, we differentiate incremental improvements from the more radical innovations that push the boundaries. In the right column, we differentiate reconfiguring and extending an existing business model from developing completely new solutions and markets with completely new business models.

I will describe the two quadrants of the “Hybrid Innovation Matrix” which are most relevant to servitization.

Adaptive and Incremental Improvements

“Adaptive and Incremental Improvements” is all about improving the performance of existing products, services and operations. Every industry has its common recipe of annual improvement of functionality, performance, speed, cost etc.

Examples:

Examples include: improvement initiatives from departments like product development, marketing service based on customer feedback following, adding new features. And PDCA, Lean, Kaizen and similar approaches to improve the quality and efficiency of our operations.

How servitization fits in:

As this is not the quadrant in which servitization takes place, I will not elaborate on this quadrant.

Pushing the Frontiers

“Pushing Frontiers” is about bigger innovations within the common business logic. In every industry, we have common pathways of how the performance of products and services develop and how (latent) customer demands evolve. We can learn from the best practices and results from others in our own industry.

Examples:

Typical examples are:

• How advanced technology continues to develop in the world of semiconductors.

• How there are hybrid and electric transmissions in cars.

• How we now have FaceID on our phones

• How we become more predictive in sales,supply chain, manufacturing and maintenance with digital capabilities.

How servitization fits in:

The early phases of the servitization journey fits in this quadrant. The service offering focuses on managing availability and condition of equipment in a more predictive manner.

Challenges:

Innovations in this quadrant often impact a large base of stakeholders in the organisation, advancing the knowledge in various disciplines, and involves bigger investments with bigger bets on the outcome.

A key challenge is to avoid obstacles at all levels in the organisation and a too narrow focus on, for example, only products or technology.

Discovery:

• Much higher levels of expertise, increasing the knowledge gaps between different stakeholders

• Finding strategic knowledge inside and outside the company

• Understanding a wider spectrum of (latent) customer needs beyond functional

• A too narrow focus, such as product technology or internal processes

• The commodity trap with innovations which hardly add customer value and are difficult to monetise.

Decision-making:

• Mitigating risks from an uncertain outcome with higher upfront investments

• Lack of digital and service mindset

• Political battles or polarised discussions

because of:

- The more qualitative arguments

- Uncertainty of outcome

- Lack of new expertise, prepared by the experts.

Implementation:

• Limited capacity to implement change fluidly in the operating organisation

• Lack of required expertise and knowledge

• Lack of digital and service mindset.

Reconfiguring and Extending Business Model

“Reconfiguring and Extending the Business model” involves a combination of entering new markets, applying new technologies, encountering new competitors and facing new political actors. These are new aspects, different from common and dominant business logic in a business or industry.

Examples:

Typical examples are:

• Low-cost airlines with a new value proposition and operating models

• Dell selling directly to the end-clients

• Storage solutions moving to cloud services

• Trucks manufacturers reducing fuel consumption by influencing truck drivers

• Fresenius (manufacturer of kidney dialysis equipment) operating entire dialysis centres in hospitals.

How servitization fits in:

As you can see from the examples, the more advanced phases of servitization extending the value offering beyond product availability perfectly fit in this quadrant.

Challenges:

The main challenge is to widen a peripheral vision escaping from the established dominant business logic.

Discovery:

• Being open to new knowledge, patterns, ideas and opportunities without being pulled back into ‘business- as usual’ by many forces

such as colleagues, clients, vendors, service suppliers and investors

• Recognising weak signals of potential trends, threats and opportunities, and when these become emergent

• Mitigating “conflict” with mainstream research activities

• Understanding and recognizing potential market disruption from immature and emerging alternatives (often at the low end of

the market).

Decision-making:

• Limited knowledge and uncertainty about unpredictable developments

• Battles between stakeholders in operating organisation and innovation organisation

• Stopping initiatives because of lack of shortterm results, in favour of initiatives closer to ‘business as usual’ with quicker results

• Not considering weak signals for potential threats, like market disruption

• Fear of cannibalism.

Implementation:

• Embedding new knowledge throughout the organisation

• Building new mindsets and competencies

• Mitigating “conflict” with mainstream operations

• Existing clients may not like the new solutions (yet).

Coevolution of New Solutions and Markets

“Coevolution of new solutions and markets” is about the radically new emerging solutions. Here, we see many different solutions and ideas popping up while it is still unclear which of the competing alternatives will emerge and become the dominant solution.

Examples:

Current examples of innovations in this quadrant are renewable energy, data-driven healthcare, mobility (including self-driving cars), Google Maps rapidly pushing away TomTom, and tachographs gradually being replaced by cloud-based applications. Other examples are PC’s displacing mini-computers and digital photography displacing analogue photography.

How servitization fits in:

I will not elaborate any further on this quadrant, as servitization in principle is not about developing these radical solutions. Even though for some industries there are actual opportunities and threats in this quadrant, in which servitization could play a role (like the Google Maps versus TomTom).

The solution: Differentiate innovation strategies with a focus on human aspects

The challenges I described concentrate on the human factors for successful discovery, decision making and implementation. They are quite different for each type of innovation in the “Hybrid Innovation Matrix”, which means we need different strategies to be successful.

I will now describe the best practices for the two types of innovation which are most relevant for servitization.

Pushing Frontiers

The name of the game here is “Managing a wider portfolio, including higher risk projects”. The following practices will help accelerate the innovations that push the frontiers.

In general:

• Establish a clear and compelling direction in which the company is heading and how that relates to the developments in the industry and market

• Build a shared concern on developments in the industry and the importance of adapting to it

• Establish cross-functional and dedicated teams of experts for specific initiatives

• Establish dedicated project management.

Discovery:

• Use advanced techniques for finding (latent) opportunities, such as design-thinking and empathic design

• Involve external experts (consultants and new partners)

Decision-making:

• Strategic level decision making

• Maintain a balanced portfolio of different types of innovations

• Apply a stage gate and review process, with clear criteria, such as;

- What initiatives should be higher risk initiatives pushing the frontiers

- In which domains to push frontiers (technology, products, services, customer experience etc.)

- Success criteria for go/no-go for the next phases

- Level of investment in different types of initiatives

• Educate stakeholders on the decision level

• Invest in further research first

• Develop solid business cases, supported by solid information

• Use advanced risk-assessment techniques

Implementation:

• Lean startup and agile development techniques

• Co-development with your best clients

• Early involvement of stakeholders from various functions

• Develop the digital and service mindsets

Pitfalls:

• Incremental improvement techniques such as PDCA and customer feedback programmes

• Not having dedicated innovation teams

Re-configuration and extending business models

The name of the game here is running “Entrepreneurial satellite teams”.

General:

• Add a transformative direction of the company, which is fairly open

• Build a shared concern for developing business models for the next growth curves

• Being flexible in an unpredictable world

• Entrepreneurial and multi-disciplinary teams decoupled from the mainstream organisation

• Allow addressing different markets or segments for (first) success

Discovery:

• Less targeted search assignments

• Techniques to reframe and thinking in “new boxes”

• Build new and broad expertise networks outside your industry

• Experiment and learn

• External contracting or outsourcing

• Scouting for successful initiatives in the market

• Develop scenarios around weak signals

Decision making:

• Reframing of the opportunities and threats

• Decentralise decision-making

• Decision-making on vision and scenarios

• Rapid prototyping

• Acquisition of early successes in the market

• Allow competing initiatives to be pursued Implementation

• Keep the new business in entrepreneurial satellite teams

• Lean startup and agile development teams

• Co-creation with the most interesting (potential) clients

Pitfalls / what does not work:

• Decision-making and resource allocation by senior leadership in the operating organisation

• Input from customer feedback programmes

• Decision-making based on business cases and stage-gate reviews

• Early integration into the current operating organisation or business model

Conclusion and takeaways

We see an increasing number of manufacturing companies committing to business innovation and servitization and allocating resources for it. A hybrid innovation strategy, focusing on the human factors of the transition will make the difference between success and failure!

If you want to boost momentum for servitization;

• Share this with your colleagues

• Assess the ideas, initiatives, progress and obstacles with the “Hybrid Innovation Matrix”

• Build a shared concern for the need for ongoing innovations in each of the quadrants

• Put the organisational and human aspects on the strategic agenda

It is a great time to be in manufacturing. We are facing exciting opportunities to make manufacturing a stronger backbone of our service-oriented economies. We have a unique opportunity to make manufacturing a great place to work and to invest in.

Jan Van Veen is Managing Director at More Momentum.

May 02, 2019 • video • Features • Astea • Kris Oldland • manufacturing • Video • field service • Internet of Things • IoT • Servitization • John Hunt

May 01, 2019 • Features • 3D printing • future of field service • Servitization

Claims that 3D printing will disrupt and revolutionise the manufacturing industry of the future, have been made since the early 1990s. For field service, that future is now writes Dr Ahmad Beltagui.

Claims that 3D printing will disrupt and revolutionise the manufacturing industry of the future, have been made since the early 1990s. For field service, that future is now writes Dr Ahmad Beltagui.

Picture this scenario: a field service engineer is called out to repair a grounded aeroplane at a remote airport. He finds the problem, but realises that repairing it will mean waiting a week for spare parts to arrive, when the client needs the plane airborne, so the contract, and perhaps his job, is on the line. Could 3D printing provide a faster solution to the problem? Today, it very likely could.

What is 3D printing?

3D printing – also known as additive manufacturing, additive layer manufacturing, rapid prototyping and rapid manufacturing – is a range of production processes that build parts in layers directly from digital designs, without the need for tooling.

These processes typically use a heat or light source to solidify plastic or metal powder, liquid polymer or plastic filament. They can produce complex geometries in small batches or even one-offs in a variety of materials, from biodegradable plastic to aerospace grade titanium. A digital, flexible future for manufacturing and service 3D printing allows production to be carried out on-demand, which is useful when spare parts are unexpectedly needed. Production in remote locations becomes possible, as NASA demonstrated by printing a wrench on the International Space Station in four hours, from a design sent digitally from Earth. 3D printing allows production of highly customised parts, from hip replacements, to dental implants to ear-phones

It enables consolidation of multiple components into one part, which delivers huge benefits in weight reduction, but also helps to streamline supply chains. For example, an aerospace part that used to be assembled from components delivered by around 20 suppliers is now designed as a single, much lighter, component. The only feasible way of producing this design is additively, rather than cutting and joining in traditional methods. Since it requires no tooling, economies of scale are less relevant, so that producing one-off parts is feasible, as Formula One teams have demonstrated with track-side 3D printers. For all of these reasons, 3D printing gives us a vision of a digital, flexible future for manufacturing and service.

The first patents for 3D printing processes were granted as early as 1986, but in recent years there has been a shift in focus from prototyping to enduse parts. Companies across the world, including IBM and Sony, had experimented, but the pioneering, and still market leading, companies were started by engineers in their spare time – Chuck Hull who invented stereolithography and founded 3D Systems, and Scott Crump, whose fused deposition modelling is the basis of industrial and desktop 3D printers made by Stratasys.

Where did it come from?

For many years 3D printing has been widely used in prototyping and new product development. Indeed, Hull’s invention was based on frustration that prototyping designs took far too long. Research suggests that, while prototyping is still the most common use, more companies are printing components and products for end-use by customers.

Where did it come from?

The first patents for 3D printing processes were granted as early as 1986, but in recent years there has been a shift in focus from prototyping to enduse parts. Companies across the world, including IBM and Sony, had experimented, but the pioneering, and still market leading, companies were started by engineers in their spare time – Chuck Hull, who invented stereolithography and founded 3D Systems, and Scott Crump, whose fused deposition modelling is the basis of industrial and desktop 3D printers made by Stratasys.

For many years 3D printing has been widely used in prototyping and new product development. Indeed, Hull’s invention was based on frustration that prototyping designs took far too long. Research suggests that, while prototyping is still the most common use, more companies are printing components and products for end-use by customers. Substantial improvements can be seen in cost, quality, speed, reliability and materials.

The industrial and commercial viability of 3D printing for volume production is being tested by companies such as General Electric, whose dedicated factories have produced over 30,000 aero-engine fuel nozzles and over 100,000 hip implants. And in some sectors, such as hearing aid production, reports suggest that every company that has not adopted 3D printing has not survived. This is only the start of a growing industry, whose annual revenues are projected to grow to over $20bn.

A growth industry – in services

Following two decades of steady development, there has been rapid growth in 3D printing revenues since around 2010. This is partly helped by the expiry of the first patents, leading to an open-source “maker” movement at the low end, which sees start-ups receiving multi-million dollar kickstarter investments and 3D printers offered for under £500 by supermarket chains, such as Aldi. Estimated global revenues for 3D printing products and services grew from $1bn in 2009 to $2bn in 2012 to over $5bn in 2015, with compound annual growth over 30% over most of this period. 3D Systems and Stratasys, who account for over a fifth of the total, saw their product revenues soar until 2014. However, the last few years have been more challenging for these companies, because the potential of 3D printing has now been recognised by companies from a variety of sectors. Driven by fear of disruption, manufacturing companies including HP, Ricoh, GE and Polaroid, as well as software companies such as Adobe, have entered the market with their own 3D printers. Meanwhile lower price competition from Asian manufacturers has increased competition in 3D Printing. The answer to the competitive challenges, as is so often the case, lies in service and servitization.

Servitization and 3D printing

With a large and growing installed base of 3D printers, there is potential for service providers to offer maintenance and operation related services. As UK based manufacturer Renishaw has reported, customers often buy a 3D printer, only to then ask for someone who knows how to use it. This is because setting up, maintaining and post-processing are highly technical tasks that require skilled personnel. Market leading companies increasingly derive their profits from digital manufacturing services, offering a full range of solutions, including design and production. They offer to take customers’ ideas through a whole digital product development and production process, effectively transforming manufacturing into a service.

So, back to our hero, the field service engineer at the remote airport, trying to fix his grounded aeroplane. In the time it took you to read this article, he could have received or downloaded the digital file for the part he needs and perhaps set up the printer to start making the part. A few hours later, he could come back to collect it and perform any post-processing required, before fitting it and letting the customer get back to business.

How far-fetched is this scenario? How far away are we from this vision of reality? Perhaps not too far. Two main barriers remain. The first is that post-processing and other technical tasks take time, effort and skill. There is, therefore, a need for managers to ensure staff are trained and have the required skills for digital production technologies. The second is intellectual property. While digital file standards make it possible to share designs, the fear that anyone can produce (or modify) a design makes companies reluctant to share.

The last few years have seen hype, unrealistic expectations and subsequent disappointment (news just in: not every home has, or is likely to have a 3D printer). However, technologies are maturing as focus shifts to refining and improving, rather than reinventing.

Global revenues for 3D printing passed $9bn last year, a large and growing proportion of which are service revenues. In short, the time to realise the benefits and take advantage of the demand for 3D printing services is now.

Dr Ahmad Beltagui is from the Advanced Services Group at Aston Business School

Apr 15, 2019 • Features • Future of FIeld Service • BigData • Christian Kowalkowski • Digitalization • Servitization • The View from Academia

Dr Christian Kowalkowski, Professor Of Industrial Marketing at Linköping University outlines how two of the biggest trends amongst manufacturers, digitalisation and servitization, are in essence two sides of the same coin and why digitalisation...

Dr Christian Kowalkowski, Professor Of Industrial Marketing at Linköping University outlines how two of the biggest trends amongst manufacturers, digitalisation and servitization, are in essence two sides of the same coin and why digitalisation requires more, not less, service and customer centricity than ever before.

The growing digital disruption is blurring industry boundaries and altering established positions of firms. While manufacturers are investing strategically in data gathering and analytics capabilities and in cloud-based platforms, many firms remain concerned about how to best address digital disruption and enable digitalisation.

Last year, General Electric cut expenses by more than 25% at its digital unit responsible for Predix, its software platform for the collection and analysis of data, which previously has been hailed as a revolutionary driver for Industry 4.0. This move highlights the difficulties involved in adopting digital technology in an industrial business. Having worked with B2B firms in diverse industries on designing and implementing service-growth strategies, I have seen both highly successful and unsuccessful cases of what I call ‘digital servitization.’

Why is it so that even many firms that run a profitable field service organisation struggle to implement digitally-enabled services?

Before looking at some key challenges, let us first define what we mean by digital servitization. As a start, we need to distinguish between digitisation, which means turning analogue into digital, and digitalisation, which refers to the use of digital technology to change the business model. A tech-savvy firm with a product-centric mindset may have little difficulty in implementing digitisation, as when record companies moved from selling LPs to CDs.

However, rather than embracing the new digital opportunities that changed the way we interact with music, most record companies then clung on to a product-centric business logic of selling CDs.

Instead of developing business models based on Internet distribution they promoted new physical media like the Super Audio CD. Ironically, their defensive stance—manifested in such things as copy protected CDs—forced many people to illegal downloading in order to conveniently access MP3 music, thereby undermining their product-centric model even further. Digital servitization, then, refers to the utilisation of digital technologies for the transformation whereby a company shifts from a productcentric to a service-centric business model.

Of course, digitally-enabled services are not new; for example, Rolls-Royce’s archetypal solution TotalCare begun in 1997 and BT Rolatruc (since 2000 part of Toyota Material Handling) created its software system BT Compass in 1993, to help its customers improve their performance. Digital technology can be a double-edged sword however. For example, many manufacturers have been carried away by the technical possibilities of telematics without having a clear service business model in mind.

Rather than crafting a compelling value proposition based on enhanced customer performance, it was tempting to give the service away for free with the hope that customers eventually would discover the value of data access and be willing to pay for it.

There are however at least three problems with such a technology-centric approach. First, as the connected installed base grows and the costs of collecting and managing data increase year by year, it becomes increasingly difficult to defend the model unless service sales start to materialise. Second, giving services away for free always reduce the perceived value of the offering in the eyes of the customer. Why should they pay for something that was previously free of charge and that competitors may still be treating as a commodity and giving away?

Third, customers typically do not have the time nor the skills to interpret and act on the data collected. The real value of Big Data only comes once it is processed. By collecting and analysing data from multiple customers, a supplier may know more about the customers’ equipment and operations then they know themselves, which creates opportunities for new advanced advisory services.

The digital dimension of service growth requires purposeful and coordinated effort. As we know, while manufacturing and conventional R&D activities can be centrally managed to achieve efficiency and standardisation, services require increased local responsiveness and closer customer relationships.

"The real value of Big Data only comes once it is processed..."

During digital servitization, however, the central organisation must take a more proactive leading role to ensure platform consistency and data quality, to provide the requisite data science skills, to support local units, and to address cyber security issues. The 2017 large-scale cyberattack (NotPetya) on Danish shipping giant Møller-Maersk, which shut down offices worldwide, illustrates the dangers of inadequately managing the latter issue.

A service manager at Toyota pointed out over ten years ago that service development “is very much IS/IT. Instead of sitting and discussing how to be able to quickly change oil in the truck, there has become very much focus on data.”

Viewing data as “the new oil” is a claim oftentimes heard. Like oil, data is a source of power. It is a resource used to power transformative technologies such as automation, artificial intelligence, and predictive analytics.

However, unlike oil, data also has other properties. We are currently seeing a shift from scarcity of information (data) to abundance of it. Data can be replicated and distributed as marginal cost, and competitive advantage can be achieved by bringing together new datasets, enabling new services. But this also creates new tensions between companies regarding the issues of generation, collection, and utilisation of data. If a customer is generating massive amounts of data that the supplier is collecting, once processed, it can be used for better serving also the customer’s competitors. In other cases, we are seeing completely new companies emerging and collecting data on behalf of their clients.

Digitalisation is beginning to have a profound impact on even the most stable businesses. Customers increasingly expect that a single provider will integrate the system of which the products are part, and that they will do so through one digital interface. Whether the platform provider is one of the established OEMs or a new software entrant might not matter. Competition may come from unexpected sources, as for example when one of the leading international standards organizations in the marine industry recently moved into platform-based services.

Oftentimes, the most formidable threat comes from disruptive innovators outside the traditional industry boundaries. An executive in a leading incumbent firm stressed that her main concern was not the competition from any established player. Instead, what kept her awake at night was the prospect of Amazon entering—and reshaping—the market. While many share the concerns of being overrun by new competitors, the threat is most imminent to those firms that lack service leadership and a clear road map for service growth.

To conclude, no firm can afford not to strategically invest in digitalisation. However, as firms compete in the digital arena, there is a risk that focus shifts too much away from service and customer centricity to new digital initiatives and units. Ten years ago, many executives sang the praises of servitization.

Today, digitalisation is the poster boy for business transformation. Given the rapid pace of innovation, it may be tempting to launch new concepts as soon as the technology is available, rather than waiting until the they have been properly piloted and customer insights gained. To reap the benefits, firms also need to understand the interplay between back end and front end, investing in both back-end development for enhanced efficiency and better-informed decision-making, and front-end initiatives to enable new services and closer customer integration.

Correctly designed and implemented, digital servitization provides benefits for companies, networks, and society at large. Successfully seizing digital opportunities, however, requires more, not less, service and customer centricity than before.

Dr Christian Kowalkowski is professor of industrial marketing at Linköping University, Sweden, and the author of Service Strategy in Action: A Practical Guide for Growing Your B2B Service and Solution Business. Find out more here.

Mar 27, 2019 • Features • Advanced Services Group • Aston Centre for Servitization Research and Practi • Data Capture • Future of FIeld Service • manufacturing • Monetizing Service • Professor Tim Baines • Servitization • tim baines

Digital technologies, IoT and digitalisation have been big topics in the manufacturing sector. Combined with services, digital seems to be the answer for a multitude of manufacturing questions, if you take the hype at face value.

But for many manufacturers, digital actually raises more questions than it answers, with one particular question at the centre: how to capture the value of digitally-enabled services?

The Advanced Services Group at Aston Business School has recently released a whitepaper on performance advisory services, which aims to cut through the hype and provide clear information and insight into how manufacturers can make the most of digitally-enabled services.

Real business insight

In this whitepaper, we wanted to reflect real business insight and real business challenges. We invited senior executives from a range of manufacturing companies - from multinationals such as GE Power and Siemens to local SMEs – for a structured debate on digitally-enabled services.

The discussion and its outcomes formed the basis of the research for the whitepaper and helped crystallise the three areas that are most important to manufacturers:

1. Performance intelligence and data as a service offering;

2. How to capture value from these services;

3. How to approach the design process to achieve success.

What are performance advisory services?

The process by which a manufacturer transforms it business model to focus on the provision of services, not just the product, is called servitization. Generally, we distinguish three types of services. Base services, such as warranties and spare parts, are standard for many manufacturers and focus on the provision of the product. Intermediate services, such as maintenance, repair and remanufacturing, focus on the condition of the product. Advanced services take a step further and focus on the capability that the product enables.

In this framework, performance advisory services are situated in between intermediate and advanced services. Typically, these are services that utilise digital technologies to monitor and capture data on the product whilst in use by the customer. These insights can include data on performance, condition, operating time and location – valuable intelligence that is offered back to the customer, in order to improve asset management and increase productivity.

Why are they attractive to manufacturers?

Performance advisory services are attractive to manufacturers because they allow the creation and capture of value from digital technologies that are likely in use already. Take the example of a photocopier - with the addition of sensors that monitor paper and toner stocks, it can send alerts when stocks are getting low. This kind of data is valuable to the customer, as it will help improve inventory management and avoid service disruptions or downtime, but it is also valuable to the manufacturer in helping them understand how the product is used, providing data that they can use to re-design products or to develop and offer new services.

Making money from performance advisory services.

Performance advisory services offer the manufacturer the potential to capture value either directly or indirectly and there is a strong business case for either. Whilst charging a fee directly for data or a service provided is compelling, the potential indirect value for the manufacturer should not be underestimated, as it can yield not only greater control and further sales, but also new and innovative offers, as well as improved efficiencies.

"Performance advisory services are situated in between intermediate and advanced services..."

In the photocopier scenario, the data generated could be sold to the customer as a service subscription, thus earning money directly.

Alternatively, the manufacturer could use the data generated for maintenance programmes or pre-emptive toner and paper sales, thus earning money indirectly. In reality, however, direct and indirect value capture are likely to go hand in hand. A prime example of this is equipment manufacturer JCB, whose machines are fitted with technology to alert the customer if the equipment leaves a predefined geographical area.

For the customer, knowing the exact location of the equipment is valuable – as it may have been stolen. But it also greatly improves efficiency for the manufacturer when field technicians are sent out for maintenance work and do not lose time locating the vehicle.

Performance advisory services - just one step on the journey to servitization

Performance advisory services present a compelling business case for manufacturers looking to innovate services through digital technologies, in order to improve growth and business resilience.

With the immediate opportunity to capture value, these digitally-enabled services are a first step for many manufacturers towards more service-led strategies and servitization.

But that is what they are – just one step on the journey to servitization. Manufacturers looking to compete through services should not stop with performance advisory services.

In the environment of a more and more outcome based economy, it is imperative to understand the potential of taking a step further to advanced services and to recognise performance advisory services as a step toward this.

The full whitepaper Performance Advisory Services: A pathway to creating value through digital technologies and servitization by The Advanced Services Group at Aston Business School is available for purchase online here.

Mar 14, 2019 • Features • Future of field servcice • Future of FIeld Service • workforce management • Servitization • The Field Service Podcast • Mark Glover • Customer Satisfaction and Expectations

In the latest Field Service Podcast, Christian Kowalkowski, Professor of Industrial Marketing at Linköping University, discusses the challenges round transitioning to a servitization business model.

In the latest Field Service Podcast, Christian Kowalkowski, Professor of Industrial Marketing at Linköping University, discusses the challenges round transitioning to a servitization business model.

In this episode, Field Service News Deputy Editor Mark Glover, speaks to Christian Kowalkowski, author of Service Strategy in Action: A Practical Guide for Growing your B2B Service and Solution Business, about the challenges businesses can face when adapting to a servitization model having been used to the more traditional transactional framework.

You can connect with Christian on his LinkedIn profile here and email him at christian.kowalkowski@liu.se

Information about the book Service Strategy in Action: A Practical Guide for Growing your B2B Service and Solution Business, including how to purchase a copy, can be found here.

Field Service News is published by 1927 Media Ltd, an independent publisher whose sole focus is on the field service sector. As such our entire resources are focused on helping drive the field service sector forwards and aiming to best serve our industry through honest, incisive and innovative media coverage of the global field service sector.

Field Service News is published by 1927 Media Ltd, an independent publisher whose sole focus is on the field service sector. As such our entire resources are focused on helping drive the field service sector forwards and aiming to best serve our industry through honest, incisive and innovative media coverage of the global field service sector.

Leave a Reply